- Welcome to The Wise Collector

- Knowledge Changes Everything!

- Buyer Beware!

- Buyer Beware!: Part II

- Caring for Your Antiques

- Coin Collecting

- McCoy Pottery

- Chinese Export Porcelain

- Frankoma Pottery

- The Arts and Crafts Movement

- Roycroft

- The Art Deco Period

- Susie Cooper Pottery

- Limoges China

- 18th C American Furniture Styles

- The Bauhaus School: Weimar 1919

- The Bauhaus School: Design & Architecture

- Portmeirion

- The End of a Century: Art Nouveau Style

- Biedermeier: The Comfortable Style

- The Souvenir Age

- A History of Ceramic Tiles

- Flow Blue China

- Collect Vintage Christmas Decorations

- An American Thanksgiving Through theYears

- How to Find an Antiques Appraiser

- Louis Prang, Father of the American Christmas Card

- Thomas Cook and the Grand Tours

- Harry Rinker's 25th Anniversary

- Mid-Century Modern

- Will Chintz China become Popular Again?

- Ireland's Waterford Crystal

- Vintage Wicker and Rattan

- Fishing Gear Collecting

- Bennington Pottery

- Identifying Pottery and Ceramic Marks

- The Art of Needlework in the Arts & Crafts Era

- The Delicious World of Vintage Cookbooks

- BLOG: RANDOM THOUGHTS

- E-BOOKS BY BARBARA BELL

- First Reader Consulting

The Art of Needlework in the Arts & Crafts Era

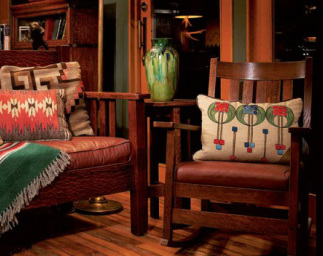

Pillow on right is from a 1910 kit. Photo by William Wright.

Traditionally, throughout history, art produced by women was usually ignored and unrecorded. Early needlework that was not used domestically for clothing or household items, most often was intended for ecclesiastical use. In these instances the person creating the robes, mitres, altar pieces and tapestries also went unrecorded and in fact was as often a monk as a nun.

In the later Middle Ages and early Renaissance, master embroiderers in Italy, Flanders and France provided the royal raiments and daily needs of wealthy classes in Europe. Many queens and high-born ladies spent their hours in fine needlework. It is said that Henry VIII passed some time in embroidery, trained by European masters.

Textiles were fragile and were used on a daily basis. They had to be cleaned (seldom by washing, however) and mended, and often replaced. Not much survived until the late 18th and into the 19th centuries when techniques for maintenance improved.

Needlework received even less respect than other art forms, because amateurs as well as professionals could do it. Little girls learned their alphabets by stitching "samplers" which also displayed their various stitchery accomplishments. The clothing for dolls originally was made as meticulous examples of the dressmaker's wares, and needed to be as well-made as the full-sized originals. Quilts were the art form for many a housewife, bride-to-be, and grandmother whose spare time could turn the mundane scraps of rough fabric into very beautiful but also functional bedcoverings. And of course, the quilting bee became a social event as well.

Today we admire and pay a great deal for the surviving tapestries, quilts and samplers of another era, because of their beauty and skill, (or innocent lack thereof), but even more so because of the bridge they provide from our time to theirs.

The Arts and Crafts movement of the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods emphasized that ART existed in daily life. This movement helped to legitimize needlework as an art form, especially in group efforts. The Movement encouraged reviving handcrafts that could be produced within the home, so that women could fully participate in the spirit of the times.

A decline in the quality of materials and dyes in the late 19th century had led to a decline in good handcrafts, exacerbated by the flight of the country girls to the city to work in factories. Where they once wove, sewed and ornamented their clothes by hand, now they stood at hulking machines in airless vast rooms, breathing in machine oils and chemical dyes. Newly arrived immigrants needed training and skills to survive in their new lives, and Settlement House workshops provided this training for thousands.

The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia engendered retrospection of American design and industry, and gradually this brought about improvement in American-made design. Regional needlework societies sprang up based on the Royal Society of Needlework (still going strong today). The New York Society of Decorative Arts (1877-1902) was one of these organizations. It hoped to be both a charitable and an instructional force for women following the Civil War.

Not only lower class women but middle class ones as well, needed to find employment as so many had lost their husbands in the war. Few options were available to women who had not been taught much more than how to keep house. But they could do needlework, and this fundamental skill could lead to tailoring, millinery, and even shopkeeping for those who could design a dress as well as make it.

In 1896 in Deerfield, MA, another group called the Society of Blue and White Needlework started a movement to preserve early American and Colonial needlework and crewel. The Society took its name from the indigo dyes used by early American settlers in their cloth. It began training local women to make reproductions of the originals. This proved a financial success, although at its peak it only employed 30 women annually. It was, however, unique.

More photos of Arts & Crafts textiles and embroidery can be found here on Pinterest.

Some of the iconic Arts & Crafts motifs found in vintage textiles include the Glasgow Rose, the Ginkgo, creeping vines and morning glory, plane trees and Prairie landscape elements, Poppy, and geometric shapes. Although extremely organic in theme, the resulting designs were precursors of Cubism, Werner Werkstatte, and Bauhaus.

Reviving the beauties of the Arts and Crafts movement, beginning in the 1980s, continues today with many wonderful artisans of the handcrafts arts. The very best are often designated by the honorific, Roycrofter (see my article on Roycroft), granted only after extreme vetting and earned by only a few.

More links with A&C needlework information:

Paint by Threads

Ann Wallace Textiles for the Home

In the later Middle Ages and early Renaissance, master embroiderers in Italy, Flanders and France provided the royal raiments and daily needs of wealthy classes in Europe. Many queens and high-born ladies spent their hours in fine needlework. It is said that Henry VIII passed some time in embroidery, trained by European masters.

Textiles were fragile and were used on a daily basis. They had to be cleaned (seldom by washing, however) and mended, and often replaced. Not much survived until the late 18th and into the 19th centuries when techniques for maintenance improved.

Needlework received even less respect than other art forms, because amateurs as well as professionals could do it. Little girls learned their alphabets by stitching "samplers" which also displayed their various stitchery accomplishments. The clothing for dolls originally was made as meticulous examples of the dressmaker's wares, and needed to be as well-made as the full-sized originals. Quilts were the art form for many a housewife, bride-to-be, and grandmother whose spare time could turn the mundane scraps of rough fabric into very beautiful but also functional bedcoverings. And of course, the quilting bee became a social event as well.

Today we admire and pay a great deal for the surviving tapestries, quilts and samplers of another era, because of their beauty and skill, (or innocent lack thereof), but even more so because of the bridge they provide from our time to theirs.

The Arts and Crafts movement of the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods emphasized that ART existed in daily life. This movement helped to legitimize needlework as an art form, especially in group efforts. The Movement encouraged reviving handcrafts that could be produced within the home, so that women could fully participate in the spirit of the times.

A decline in the quality of materials and dyes in the late 19th century had led to a decline in good handcrafts, exacerbated by the flight of the country girls to the city to work in factories. Where they once wove, sewed and ornamented their clothes by hand, now they stood at hulking machines in airless vast rooms, breathing in machine oils and chemical dyes. Newly arrived immigrants needed training and skills to survive in their new lives, and Settlement House workshops provided this training for thousands.

The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia engendered retrospection of American design and industry, and gradually this brought about improvement in American-made design. Regional needlework societies sprang up based on the Royal Society of Needlework (still going strong today). The New York Society of Decorative Arts (1877-1902) was one of these organizations. It hoped to be both a charitable and an instructional force for women following the Civil War.

Not only lower class women but middle class ones as well, needed to find employment as so many had lost their husbands in the war. Few options were available to women who had not been taught much more than how to keep house. But they could do needlework, and this fundamental skill could lead to tailoring, millinery, and even shopkeeping for those who could design a dress as well as make it.

In 1896 in Deerfield, MA, another group called the Society of Blue and White Needlework started a movement to preserve early American and Colonial needlework and crewel. The Society took its name from the indigo dyes used by early American settlers in their cloth. It began training local women to make reproductions of the originals. This proved a financial success, although at its peak it only employed 30 women annually. It was, however, unique.

More photos of Arts & Crafts textiles and embroidery can be found here on Pinterest.

Some of the iconic Arts & Crafts motifs found in vintage textiles include the Glasgow Rose, the Ginkgo, creeping vines and morning glory, plane trees and Prairie landscape elements, Poppy, and geometric shapes. Although extremely organic in theme, the resulting designs were precursors of Cubism, Werner Werkstatte, and Bauhaus.

Reviving the beauties of the Arts and Crafts movement, beginning in the 1980s, continues today with many wonderful artisans of the handcrafts arts. The very best are often designated by the honorific, Roycrofter (see my article on Roycroft), granted only after extreme vetting and earned by only a few.

More links with A&C needlework information:

Paint by Threads

Ann Wallace Textiles for the Home

Web Hosting by iPage. The copyright of the articles in The Wise Collector is owned by Barbara Nicholson Bell. Permission to republish any articles herein online or in print must be granted by the author in writing.